World Migration Report 2024: Chapter 3

Africa

Migration in Africa involves large numbers of international migrants moving both within and from the region.4 As shown in Figure 1, most international migration occurs within the region. The latest available international migrant stock data (2020)5 show that around 21 million Africans were living in another African country, a significant increase from 2015, when around 18 million Africans were estimated to be living outside of their country of origin but within the region. The number of Africans living in different regions also grew during the same period, from around 17 million in 2015 to over 19.5 million in 2020.

Figure 1 shows that since 2000, international migration within the African region has increased significantly. Since1990, the number of African migrants living outside of the region has more than doubled, with the growth in Europe most pronounced. In 2020, most African-born migrants living outside the region were residing in Europe (11 million), Asia (nearly 5 million) and Northern America (around 3 million).

One of the most striking aspects to note about international migrants in Africa, as shown in Figure 1, is the small number of migrants who were born outside of the region and have since moved there. From 2015 to 2020, the number of migrants born outside the region remained virtually unchanged (around 2 million), most of whom were from Asia and Europe.

Source: UN DESA, 2021.

Notes: This is the latest available international migrant stock data at the time of writing. “Migrants to Africa” refers to migrants residing in the region (i.e. Africa) who were born in one of the other regions (e.g. Europe or Asia). “Migrants within Africa” refers to migrants born in the region (i.e. Africa) and residing outside their country of birth, but still within the African region. “Migrants from Africa” refers to people born in Africa who were residing outside the region (e.g. in Europe or Northern America).

In Africa, the proportion of female and male migrants in the top destination countries is similar, with only slight differences between countries. The most visible exception is Libya, where the share of male immigrants is significantly higher than that of female immigrants. This dynamic is broadly similar in the top 10 origin countries in Africa, apart from Egypt – the top country of origin in the region – which has a far greater share of male emigrants compared to females.

Source: UNHCR, n.d.a.

Note: This is the latest available international migrant stock data at the time of writing. “Proportion” refers to the share of female or male migrants in the total number of immigrants in destination countries (left) or in the total number of emigrants from origin countries (right).

Displacement within and from Africa remains a major feature of the region, as shown in Figure 3. Most refugees on the continent were hosted in neighbouring countries within the region. The top 10 countries in Africa, ranked by the combined total of refugees and aslyum-seekers both hosted by and originating from that country, are shown in Figure 3. South Sudan continued to be the country of origin of the largest number of refugees in Africa (around 2.3 million) and ranked fourth globally, after the Syrian Arab Republic, Ukraine and Afghanistan. The Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Sudan were the origin of the second and third largest number of refugees on the continent (more than 900,000 and over 800,000, respectively). Other origin countries of a significant number of refugees include Somalia (nearly 800,000) and the Central African Republic (more than 748,000). Among host countries, Uganda – with nearly 1.5 million – continued to be home to the largest number of refugees in Africa in2022. Most refugees in Uganda originated from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In addition to producing a significant number of refugees, countries such as the Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo also hosted large refugee populations by end of 2022 (nearly 1.1 million and over half a million, respectively). Ethiopia, with nearly 900,000 refugees, was the third largest host country of refugees in Africa in 2022.

Source: UNHCR, n.d.a.

Note: “Hosted” refers to those refugees and asylum-seekers from other countries who are residing in the receiving country (right‑hand side of the figure); “abroad” refers to refugees and asylum‑seekers originating from that country who are outside of their origin country. The top 10 countries are based on 2022 data and are calculated by combining refugees and asylum‑seekers in and from countries.

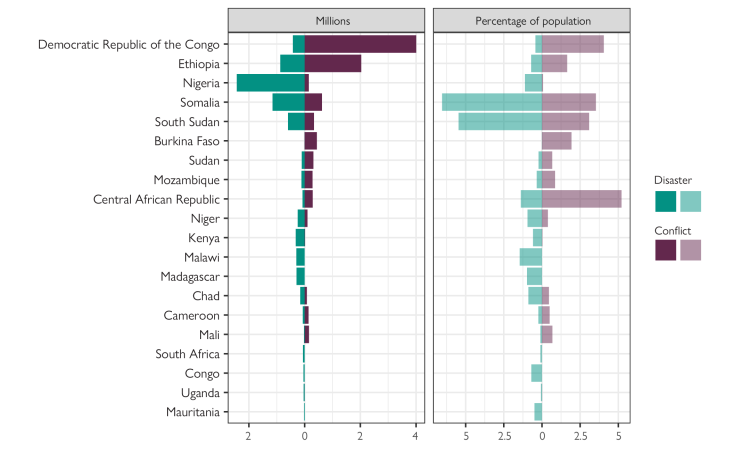

Consistent with previous years, the majority of internal displacements in Africa in 2022 occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, with most triggered by conflict and violence. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (over 4 million) and Ethiopia (more than 2 million) had the largest internal displacements due to conflict and violence. Somalia, with 621,000 displacements caused by conflict, had the third largest in the region. The largest disaster displacements were recorded in Nigeria (around 2.4 million), followed by Somalia (1.2 million), Ethiopia (873,000) and South Sudan (596,000).

Source: IDMC, n.d.; UN DESA, 2022.

Notes: The term “displacements” refers to the number of displacement movements that occurred in 2022 not the total accumulated stock of IDPs resulting from displacement over time. New displacement figures include individuals who have been displaced more than once and do not correspond to the number of people displaced during the year.

The population size used to calculate the percentage of new disaster and conflict displacements is based on the total resident population of the country per 2021 UN DESA population estimates, and the percentage is for relative illustrative purposes only.

Key features and developments in Africa6

North Africa

Irregular migration to, through and from North Africa remains the defining feature of migration dynamics in the subregion, with many migrants suffering human rights abuses. North Africa is a point of departure for thousands of migrants who embark on journeys, largely along the west and central Mediterranean routes. Across the subregion, especially in countries of transit such as Libya, well-established smuggling and trafficking networks have developed over the years.7 In Libya, at points of maritime departure toward Europe, beatings, torture and forced labour of migrants have been well documented.8 Women and girls in particular are at heightened risk of gender-based violence, especially during desert crossings and at border areas.9 Thousands of migrants have also lost their lives. The central Mediterranean route is the deadliest route globally, with more than 20,000 migrants having died or disappeared along this route between 2014 and 2022.10 In response to these ongoing challenges along the central Mediterranean route, the European Commission proposed a European Union action plan in November 2022, which outlines “20 measures designed to reduce irregular and unsafe migration, provide solutions to the emerging challenges in the area of search and rescue and reinforce solidarity balanced against responsibility between member States.”11 While some actions in the Plan – including those focused on supporting as well as facilitating the sharing of responsibility – have been welcomed by a range of actors, others, including some NGOs, have criticized it as unworkable and a recycling of old mistakes.12

Recent attacks on sub-Saharan African migrants living in parts of North Africa highlight xenophobia and racism in parts of the subregion. In Tunisia, for example, political rhetoric in early 2023, accusing migrants from sub-Saharan Africa of fostering crime and threatening the demographic composition and national identity of the country, led to racist violence within the country.13 In addition to verbal and physical abuse, some migrants lost their jobs and others were evicted from their homes.14 This rhetoric – reminiscent of the anti-immigrant political discourse in several countries across Europe in recent years – has been spurred on by some media outlets and online platforms in Tunisia.15 Several countries, including Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Mali organized repatriation flights for their citizens who were desperate to leave.16 The hate speech and violence against sub- Saharan African migrants prompted the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination to issue a statement calling on Tunisia to “combat all forms of racial discrimination and racist violence against black Africans, especially migrants from the south of the Sahara and black Tunisian citizens.”17 A range of abuses and violence have also been documented in Libya, with a 2022 report of the United Nations Human Rights Office highlighting how migrants are routinely subjected to racism, xenophobia, criminalization and other human rights violations.18

International remittances remain significant to North Africa and are major sources of foreign exchange for several countries in the subregion. Remittances became even more important following the onset of COVID-19, as revenues from tourism – which had long been vital for countries such as Egypt – dried up due to mobility restrictions. The subregion has a long history of emigration, with large numbers of emigrants living in Europe and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) States. For example, Saudi Arabia was home to nearly one million Egyptians in 2020.19 In 2022, Egypt is estimated to have received more than 28 billion United States dollars (USD) in international remittances, making it the seventh largest recipient after India, Mexico, China, the Philippines, France and Pakistan.20 Morocco, which ranks among the top 20 recipient countries of international remittances globally, is estimated to have received over USD 11 billion in 2022, accounting for 8 per cent of its GDP.21

North Africa is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, with the subregion affected by both slow‑onset and rapid-onset events, resulting in significant displacements in recent years. The subregion has experienced significant warming over the last several decades, while at the same time seeing its rainfall decrease during the wet season, particularly in countries such as Libya, Algeria and Morocco.22 While the Middle East and North African (MENA) countries are some of the most impacted by climate change, they are considered among the least prepared.23 The World Bank’s 2021 Groundswell report projects that without tangible action on climate and development, millions of people across North Africa could be forced to move within their countries as a result of climate change.24 Already one of the most water-stressed parts of the world, climate change could further exacerbate this reality, and we are already seeing impacts on agriculture and food production in the subregion. Increased water scarcity could also escalate existing conflicts and violence. In Libya, local militias have weaponized water scarcity, including using water infrastructure for leverage against the central government and other rivals.25 Moreover, the protracted conflict in Libya has left it with low adaptive capacity, and the combination of conflict and climate change impacts have disrupted food production and displaced many from their communities.26 Countries such as Algeria and Morocco have experienced significant displacements triggered by droughts and wildfires. By end of 2022, wildfires induced 9,500 displacements in parts of northern Morocco, and in the same year, 2,000 displacements – also due to wildfires – were recorded in north-eastern Algeria.27 Wildfires also destroyed significant swaths of land, especially in Morocco, where they ruined more land in 2022 than in the previous nine years combined.28

Conflict and violence continue to cause cross-border and internal displacement, while the subregion also hosts large numbers of refugees in protracted situations. Displacement in the subregion is largely driven by conflict and violence.29 In the Sudan, intense fighting between the country’s military and its main paramilitary force erupted in April 2023, killing hundreds of people and forcing thousands to flee for safety, the majority within the country but others across borders, including to neighbouring countries such as South Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia and Chad.30 Prior to this, the Sudan had seen violent clashes between clans and communities over access to land and control of resources, especially in West Darfur.31 At the end 2022, the Sudan had more than 3.5 million IDPs and over 300,000 displacements as a result of conflict and violence.32 The Sudan also hosts one of the largest refugee populations in Africa, and in 2022, the country was home to around 1 million refugees and asylum-seekers.33 Most came from South Sudan, Eritrea, the Syrian Arab Republic and Ethiopia. Meanwhile, in Libya, although the October 2020 ceasefire agreement between warring factions remains intact, it has not been fully implemented, and the country continues to experience political instability, albeit with a significantly reduced number of people living in internal displacement as a result of conflict and violence.34 Libya had around 135,000 conflict IDPs in 2022, the lowest since 2013.35

Eastern and Southern Africa

The subregion has experienced a significant increase in intraregional migrants, driven in part by free movement arrangements. The number of migrant workers residing within East African Community (EAC) countries reached nearly 3 million in 2019, growing from just under 1.5 million in 2010.36 Within the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the number increased to over 3 million, doubling since 2010.37 Efforts to enhance integration in the subregion – including through the East African Common Market Protocol, which entered into force in 2010 and aims to realize the free movement of persons, labour, capital, services and goods – have been vital to removing barriers to employment. While not fully implemented across all countries, many citizens of the EAC have the right to entry and work within the Community and have access to the free processing of work permits.38 To further bolster integration and facilitate labour mobility within the subregion, several States within the EAC have also advanced frameworks on mutual skills recognition, playing “an important role in providing migrant workers access to other markets.”39 In 2021, IGAD member States adopted a Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, which is also the first free movement protocol globally to address the movement of people across borders in response to the adverse impacts of climate change.40 Simultaneously, and in recognition of the significance of pastoralism as one of the key forms of livelihood in the region, IGAD member States adopted a Protocol on Transhumance, which has the objective of facilitating free, safe and orderly cross-border mobility of transhumant livestock and herders.41 The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) also has protocols on free movement, but their implementation has been slow.42 There has been renewed impetus, however, to facilitate free movement among COMESA member States, with two task forces created to help advance the implementation of the protocols.43

While free movement protocols have been instrumental in enabling people to easily move across borders, irregular migration – both within and from the subregion – remains a challenge. In Eastern Africa, irregular migration often occurs along four key routes: the southern route, towards Southern Africa (mainly to South Africa); the Horn of Africa route (movements within the Horn of Africa); the northern route, towards North Africa and Europe; and the eastern route, towards the Arabian Peninsula (mainly to Saudi Arabia).44 Often facilitated by smugglers, the journeys migrants embark on along these routes are fraught with risks. Along the southern route to South Africa, for example, migrants encounter multiple challenges and risks, including having to make unexpected payments to brokers; they often lack sufficient funds for basics such as food; and some experience physical, sexual, psychological and other abuses.45

Climate change induced disasters such as droughts, hurricanes and floods have devastated livelihoods in Eastern and Southern Africa, while also displacing millions of people in the subregion. By March 2023, the East and Horn of Africa subregion was experiencing a record drought, the worst in more than 40 years.46 Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia have been most affected, with the drought coming on top of years of insecurity and conflict, particularly in Somalia and Ethiopia. The consequences have been far-reaching, and across the IGAD subregion 27 million people were highly food insecure, with predictions of a famine in Somalia in 2023.47 By May 2023, more than 2 million people had been internally displaced due to drought in Ethiopia and Somalia (combined), while over 866,000 refugees and asylum-seekers in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia were living in drought-affected areas at the start of the year.48 In response to the growing intensity of the adverse effects of climate change and its expanding geographical scale of climate-induced mobility, more than 10 States of the East and Horn of Africa subregion, supported by IGAD and the EAC, came together in September 2022 in Kampala, Uganda, and signed a historic new Declaration: the Kampala Ministerial Declaration on Migration, Environment and Climate Change (KDMECC).49 The Declaration lists 12 commitments articulated by the signatory States and five requests to the parties to the UNFCCC, under a collaborative framework that concretely addresses climate-induced mobility whilst driving forward the sustainable development of States. In Southern Africa, disasters linked to climate change, including cyclones, have become more frequent and intense.50 Cyclone Freddy, for example, wreaked havoc in Malawi, Mozambique and Madagascar in early 2023 and was one of the longest-lasting tropical cyclones ever recorded.51 The cyclone claimed more than 500 lives, and displaced over 500,000 people in Malawi alone.52

Newly emerged and longstanding armed conflicts remain significant drivers of displacement in the subregion. Eastern Africa has been beset by conflicts for decades and remains one of the most conflict-affected subregions in the world. The decades-long civil war in Somalia, increased Al-Shabab attacks as well as government counter-insurgency operations in response made 2022 the deadliest year in the country since 2018, while also triggering mass displacement.53 An estimated 3.9 million people were living in internal displacement in Somalia at the end of 2022, a rise of nearly 1 million from the year prior.54 In South Sudan, despite the 2018 peace agreement, intercommunal violence remains widespread and has resulted in considerable internal and cross-border displacement, with most internal displacements in 2022 taking place in Jonglei, Upper Nile and Unity states.55 The country continued to be among the largest origin countries of refugees in Africa (more than 2 million), with most residing in Uganda, the Sudan and Ethiopia.56 At the same time, Ethiopia underwent a brutal civil war in the north of the country, resulting in significant loss of lives, destruction of property and the displacement of millions of people. The armed conflict that broke out in the Sudan in April 2023 (see North Africa section) has resulted in significant internal and cross-border displacement, forcing many Sudanese to seek refuge in Eastern African countries such as South Sudan and Ethiopia. At end of July 2023, South Sudan alone had received nearly 200,000 new refugee arrivals from the Sudan.57 The conflict has also meant that many refugees who had been hosted by the Sudan, including from countries such as Ethiopia, have fled to neighbouring countries or returned home.58 A November 2022 peace deal resulted in a ceasefire, restoring security in the worst-affected areas of Afar, Amhara and Tigray, although significant humanitarian needs remain.59 The Office of the United Nations Special Envoy to the Horn of Africa, together with IGAD and in partnership with United Nations agencies, have developed a Regional Prevention and Integration Strategy for the Horn of Africa, with provisions for the establishment of a Regional Climate Security Coordination Mechanism with the primary objective to support IGAD and strengthen the capacities of regional, national and local actors to address the linkages between climate, peace and security.

Gulf States remain key destination countries for migrant workers from the subregion, particularly those from Eastern Africa. Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda are the main origin countries of migrant workers from the subregion to GCC States, with most working in hospitality, security, construction and retail.60 Driven by high rates of unemployment and underemployment, as well as the prospect for higher wages, many young people seek employment opportunities in the Gulf.61 The Gulf’s close proximity, coupled with the increasing difficulty of gaining entry to previously traditional destination countries (for example, the United Kingdom and the United States), have made GCC States attractive labour migration options. The proliferation of recruitment firms across Eastern Africa, as well as several bilateral labour agreements, have also contributed to the significant increase in labour migration to the Gulf.62 Regular and irregular labour migration from Eastern Africa to the Gulf are both prevalent and have increased over time, making the eastern corridor one of the busiest maritime migration routes in the world.63 Labour migration to the Gulf has resulted in a substantial increase in remittances, especially to countries such as Kenya and Uganda. Remittances to Kenya and Uganda climbed to more than USD 4 billion and over USD 1.2 billion, respectively, in part due to increased inflows from GCC States.64 Saudi Arabia now ranks only behind the United Kingdom and the United States as the third largest source of remittances to Kenya.65 While several GCC States are implementing measures to reduce abuse of migrant workers – including reforming the Kafala system – the mistreatment and exploitation of migrant workers remains widespread.66 Some of the most prevalent abuses include physical and sexual violence, restriction of freedom, abusive and coercive employment practices and deceptive, unfair and unsafe work environments.67

West and Central Africa

Parts of the subregion remain hotspots of conflict, insecurity and violent extremism, with the Sahel continuing to be the most volatile. The Sahel region of Africa, which stretches from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, has long been an area of significant migration flows. The region faces ongoing crises including climate and environmental degradation, desertification, political and institutional instability, a lack of basic services, intercommunity conflicts between nomadic herders and farmers and the rapid rise of violent extremism.68 The Sahel has long been affected by insecurity, characterized by armed conflict, military clashes and recurrent violence instigated by Islamist groups. The Central Sahel is the most affected by violence, with many civilians killed in 2022 alone.69 The Central Sahel was thrown into further turmoil in 2021 after military coups in Burkina Faso and Mali, which resulted in their suspensions from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union.70 In 2022, there were more than 2.9 million refugees and internally displaced persons in Mali, Burkina Faso and the Niger.71 Clashes have spilled over to neighbouring countries such as Togo, Côte d’Ivoire and Benin. Moreover, children have been targeted by non-State armed groups in Mali, Burkina Faso and the Niger with hundreds, many of them girls, abducted.72 In addition to ongoing conflict and insecurity, West and Central Africa is affected by an interplay of other factors, including climate change and food insecurity. Rainfall in the Sahel, for example, has decreased by over 20 per cent since the 1970s, making this part of Africa one of the most prone to droughts.73 At the same time, parts of the subregion have experienced significant sudden-onset disasters, which have displaced millions of people. Nigeria, for example, had the largest number of internal displacements due to disasters in sub-Saharan Africa in 2022 (more than 2.4 million).74 This was also highest figure recorded in Nigeria in ten years.75 The displacements were largely the result of floods between June and November 2022.76

Each year, tens of thousands of migrants from West and Central Africa undertake highly risky irregular migration journeys, as many try to make their way to Europe. Migrant abuses are common on these journeys, including along several key routes between West and Central Africa and North Africa, the Sahara, or during sea crossings.77 Irregular migration from West and Central Africa often occurs along the central Mediterranean route (sea crossings from North African countries and the Middle East mainly to Italy); the western Mediterranean route (consisting of several subroutes linking Morocco and Algeria to Spain); and the west African Atlantic route (from West African coastal countries and Morocco to the Canary Islands in Spain).78 In 2022 alone, nearly 2,800 deaths and disappearances were recorded along the central Mediterranean route, the west African Atlantic route, the western Mediterranean route and other routes in West and Central Africa.79 Due to limited search and rescue operations, these figures are very likely an underestimate. The west African Atlantic route is considered very dangerous because of the length of the journey, with migrants often stuck at sea for long periods on inadequate boats in areas of the Atlantic Ocean lacking dedicated rescue operations.80 More than 29,000 nationals from West and Central Africa arrived in Europe along these various routes in 2022, with most (58%) arriving in Italy, 17 per cent in Spain, 21 per cent in Cyprus and Malta and 4 per cent in Greece.81

In West and Central Africa, intraregional migration remains a prominent feature of migration dynamics, with most international migrants living within the subregion. West and Central Africa was home to more than 11 million international migrants in 2020, with the large majority coming from countries within the subregion.82 The subregion is home to half a billion people, 40 per cent of whom are under the age of 15.83 The number of young people is projected to grow further, which could be a demographic dividend or further put pressure on a subregion already struggling with high rates of unemployment, especially among young people. Moreover, West and Central Africa suffers from high levels of poverty and large gender gaps when it comes to areas such as workforce participation and education attainment.84 Intraregional migration in West Africa – estimated to be around 70 per cent of migration flows – is to a large extent due to labour mobility and involves temporary, seasonal and permanent migration of workers, with countries such as Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana the key destinations.85 The ECOWAS free movement protocol has played a key role in facilitating labour mobility in West Africa; in fact, all countries in the subregion are members of this regional economic community, which means that citizens of ECOWAS member States have the right to enter, reside in and establish economic activities in another member State.86 However, while ECOWAS has made significant strides when it comes to enabling free movement, the full implementation of its protocol is yet to be realized. The protocol continues to be undermined by a range of challenges, including those related to varying national interests and poor infrastructure, among others.87 The Economic Community of Central African States also has a protocol of free movement; however, progress on its implementation has been slow and not a priority of Central African States, several of which continue to struggle with significant political instability.88 Nonetheless, countries such as Equatorial Guinea and Gabon – with large lumber and oil industries – attract a significant number of migrant workers from the subregion.89

The 2022 football World Cup highlighted some of the benefits of migration with many players of West African descent, for example, proving critical to national teams in Europe. National teams across the world comprise players of diverse backgrounds, including players representing countries in which they were not born, and others who are children of migrants. The 2022 World Cup in Qatar had the largest share of foreign‑born players in the tournament’s history, with 137 of the 830 players (17%) representing countries in which they were not born.90 Countries such as Morocco and Qatar had the highest number of foreign-born players.91 Across European national teams, of players who were not foreign born, many were of African descent.92 For example, several star players on the French team, including Kylian Mbappé and Paul Pogba, have family links to the subregion.93 However, it is important to also highlight that for the vast majority of young people in the subregion with the desire to play football in Europe, the opportunities to migrate and successfully join football clubs in regions such as Europe are extremely limited. For most, their aspirations are often fraught with significant risks and dangers. Migrant smugglers and traffickers can take advantage of their dreams to play in big leagues in Europe, luring thousands from the subregion with false hopes of becoming professional footballers.94 Often masquerading as football agents, they charge large sums of money to facilitate their journeys to Europe, only to abandon them upon arrival; other such migrants end up as victims of forced labour or sexual exploitation, among other abuses and violations.95