World Migration Report 2024: Chapter 5

Appendix B. Country case studies by United Nations region

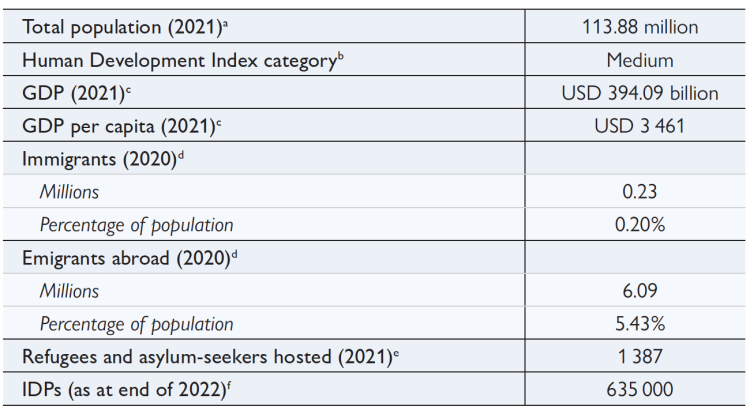

Country case study (Latin America): Colombia. Regularization programming

Sources: (a) UN DESA, 2022; (b) UNDP, 2020; (c) World Bank, n.d.; (d) UN DESA, 2021; (e) UNHCR, n.d.; (f) IDMC, 2023.

Major impacts on populations

Since 2015, more than six million people have fled the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela from an unfurling socioeconomic, political and humanitarian crisis.86 On 8 February 2021, the Colombian Government, with assistance from the Government of the United States in the form of funding and equipment, announced the start of a large regularization programme.87 It is estimated that at least 56 per cent of the 1.7 million Venezuelans living in Colombia at the end of 2020 did not have regular status.88 For qualifying applicants, a temporary protection permit (TPP) was granted, which guarantees temporary protection status (TPS) for 10 years, as well as access to basic services such as education, housing and health care.

In addition to providing temporary, long-term legal status to Venezuelans living in irregular situations in Colombia as of the end of January 2021,89 TPS was also extended to Venezuelans who would enter Colombia with a passport through an officially recognized border checkpoint for the following two years, until January 2023.90 Since the dissolution of diplomatic ties between Colombia and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela in February 2019,91 as well as the domination of armed groups along the countries’ shared borders,92 official channels to document rights violations of displaced peoples are far and few between.

Temporary protection granted to Venezuelan migrants represents a new policy category provided by the Colombian Government and provides a solution for many Venezuelans fleeing the crisis in their home country.93 Although described by the office of the Colombian presidency as apolitical and humanitarian,94 it represents a response to the growth in the number of irregular Venezuelan migrants and the low acceptance rate – only 0.04 per cent – of asylum claims prior to 2021.95

Key challenges for authorities and practitioners

While notable benefits of TPS for Venezuelan nationals in Colombia have included a reduction in the threat of trafficking,96 as well as the possibility of formal employment,97 several challenges remain. Despite the possibility of transitioning from informal to formal labour markets, xenophobia and discrimination still impede Venezuelans from attaining formal labour contracts. Particularly for Venezuelan women in Colombia, unemployment reached nearly 35 per cent in 2021 – up 6 per cent from 2019,98 and higher than unemployment for Colombian women – due to both the economic weakening caused by COVID-19,99 and disproportional demand for jobs outweighing the supply of available employment opportunities.100 Other impediments lie within the integration processes themselves, with many reporting difficulties accessing education, health services and even adequate housing in certain parts of the country.101

Some critics have argued that by addressing all Venezuelan displacement in Colombia as an issue of migratory management, the TPS disadvantages those fleeing the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela who may have otherwise qualified for international protection in line with existing legal frameworks (such as the Cartagena Declaration). This might present challenges in dealing with the gap between rights afforded to refugees and those provided to Venezuelans under TPS, and could impact how other governments respond to regional humanitarian needs.102

Finally, one of the reasons why Venezuelans are often smuggled out of the country, when fleeing violence and persecution, is that presenting themselves at official border points can be dangerous.103 The inability to document one’s presence at a formal border point, which is a requirement to be granted TPS for new arrivals, may result in a new group of irregular migrants.

Good practices

Colombia’s implementation of TPS has been commended as being carried out at unprecedented magnitude and speed.104 It is also an important step in securing human rights and durable solutions for migrants.105 By November 2022, over 1.6 million TPPs had been approved.106 With permits, card holders can officially access the nationalized health system. As well, they can access financial services, such as opening a bank account, purchasing a home and accessing a loan,107 which, despite its incipient legality prior to the issuing of cards, many banks and financial providers refused, insisting on formal identification documents and credit histories.108

The successful regularization of Venezuelans in Colombia could, in many ways, be attributed to the unified, government-led effort, directed by the office of the presidency and with the support provided by the Government of the United States, to provide status to a substantial population of irregular, undocumented migrants within its borders.109 Colombia’s temporary protection scheme is the largest-scale effort of its kind to offer protection to a single nationality of displaced people and has been acclaimed a significant example of an effective response to displacement.110

Country case study (Northern America): Canada. Gender Equality in Migration

Sources: (a) UN DESA, 2022; (b) UNDP, 2020; (c) World Bank, n.d.; (d) UN DESA, 2021; (e) UNHCR, n.d.; (f) IDMC, 2023.

Major impacts on populations

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the Canadian agency responsible for migration, has a longestablished tradition of promoting gender equality within migration management and governance mechanisms that, in turn, directly impact the lives of migrants. Particularly with gender-sensitive frameworks and processes that seek to directly support migrant women and gender diverse populations, such as the Gender Results Framework (GRF)111 and Gender-based Analysis+ (GBA+),112 approaches are applied to better understand the ways certain populations are particularly vulnerable and heavily disenfranchised throughout migratory processes, specifically in destination countries such as Canada.

These structures have led to pilot projects, such as the Racialized Minority Newcomer Women Pilot,113 the Home Child Care Provider Pilot and the Home Support Worker Pilot,114 which seek to not only to support women’s employment through the creation of new opportunities, but also recognize the central role that women play in the reproductive care economy. Further initiatives that protect and support gender equality include the Rainbow Refugee Assistance Partnership and the Assistance to Women at Risk Program,115 which support the creation of migration pathways for vulnerable individuals fleeing violence and persecution. Once in Canada, settlement programmes through the IRCC offer myriad support systems to vulnerable populations as they integrate into a new country, such as childcare, transportation assistance, women-only employment and language support programmes, pathways to report domestic abuse and other gender-based violence prevention.116

Key challenges for authorities and practitioners

The GRF reports that unpaid work, the proportion of people in part-time jobs and low-wage employment disproportionately impact women.117 Within these data sets, it may be necessary to incorporate additional demographic data to identify intersectional factors leading to poor outcomes, as well as possible ameliorations.

According to data from January 2021, labour underutilization had increased by 1 per cent to 18.4 per cent,118 with many of those affected being temporary migrants. COVID-19 associated lockdowns and employment restrictions had a harder impact on women, youth, racialized communities and migrants; this has led to calls for devoting more attention to the efficacy of settlement services, which are currently struggling as a result of the pandemic.119 This has also reinvigorated discussions on the need to facilitate the transition from temporary to more permanent residence status for some migrant groups, which, aside from better labour market integration, affords stronger worker protections.

Good practices

Many programmes, mechanisms and resources have been instrumentalized to advocate for gender equality in migration management. The focus has been on creating tangible opportunities, including employment pathways and protections, for those most disadvantaged by gendered inequalities upon settlement in Canada, such as LGBTQIA+ individuals. These initiatives include the introduction of pedagogic programming to train internal staff on the importance of inclusivity, respect and the differences between gender identity, gender expression and sexual orientation, as is the case with the Gender Diversity and Inclusivity Online Training Course.120 Furthermore, a commitment to inclusive language in official communication platforms has held steadfast, particularly through the introduction of a gender neutral designation, or an “X” instead of a selected binary gender, on official documents.121 For many migrants, these supports provide valuable protection from violence and prejudice resulting from gendered inequalities.

Country case study (Europe): Switzerland. Inclusion of irregular migrants

Sources: (a) UN DESA, 2022; (b) UNDP, 2020; (c) World Bank, n.d.; (d) UN DESA, 2021; (e) UNHCR, n.d.; (f) IDMC, 2023.

Major impacts on populations

Some cities around the world have decided to recognize individuals without immigration status as part and parcel of the functioning of the city themselves. While this approach doesn’t typically provide legal status to an undocumented migrant, it enables access to services and facilitates proof of city membership. The city of Zurich created such an urban identity card programme called Züri City Card (ZCC),122 which will cost a total of CHF 3.2 million.123 Pushback from rural municipalities circumscribed within the canton of Zurich has prevented the cantonal government from implementing a regularization programme such as Geneva’s Operation Papyrus, launched in 2017.124 Instead, the city of Zurich, where it is estimated that more than 10,000 undocumented migrants reside, will offer cardholders the possibility to access public services without the fear of being reported to immigration authorities.125 In specific terms, the identity card confirms identity and place of residence, providing a form of local membership, while officially affirming an entitlement to access essential services, including health care.126

Key challenges for authorities and practitioners

The inspiration for Zurich’s city initiative to support and protect undocumented migrants come from the United States “sanctuary cities” that create spaces within cityscapes to allow irregular migrants to access services without fear of being reported to immigration authorities.127 Importantly, the ZCC was conceived by local actors who then formed an association (Züri City Card Association) and presented to the city government of Zurich. The Züri City Card Association was hesitant initially to cooperate with the cantonal government as the city and canton handle issues of irregular migration very differently.128 In turn, key challenges throughout the implementation process of this initiative focused specifically on this interaction between city officials, societal actors, canton and confederation levels, as multilevel governance does not exist within the City of Zurich.129

While the City of Zurich has attempted to take on a coordination role between the Züri City Card Association and cantonal and confederation authorities, local civil society organizations, such as the Sans-Papiers Anlaufstelle Zürich (SPAZ),130 have taken on a large role in supporting undocumented migrants with access to services. This includes claiming social assistance, securing rental accommodation and accessing health care.131 As the pilot phase of the ZCC is set to last four to five years, after the positive local referendum vote from May 2022, successful implementation of the initiative over the long term is a crucial next step for the city government to ensure that this identification tool can successfully recognize undocumented migrants for the role they play in the community.

Good practices

While support for the initiative could not be found within the canton of Zurich at large, this city-proposed project gained success based on the “horizontal venue shopping” that the Züri City Card Association engaged in, which led to the identity card finding its way onto the city’s local political agenda.132 Importantly, many migrants who have come to Switzerland without status, or who have lost status once in the country, do not have the right to apply for residency, despite the integral role they play in Switzerland’s economy: SPAZ expressed how the Swiss economy could potentially “fall apart” without the support of undocumented migrants’ labour.133

The initiative has allowed more than 10,000 undocumented migrants living in the city of Zurich over the course of the pilot programme to have a strengthened sense of security when accessing essential services and seeking social support.134 While regular pathways for migration for many, particularly for those working in low-wage sectors,135 remain narrow, support within local contexts is more important than ever. Inspired by the ZCC, discussions have commenced on the creation of a similar card in the nation’s capital city of Bern, as well as in Basel.

Country case study (Africa): Burkina Faso. Internal displacement due to conflict and violence

Sources: (a) UN DESA, 2022; (b) UNDP, 2020; (c) World Bank, n.d.; (d) UN DESA, 2021; (e) UNHCR, n.d.; (f) IDMC, 2023.

Major impacts on populations

Beginning in 2015, a worsening security situation in the central Sahel caused by overlapping attacks on civilians from armed groups associated with the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda, as well as other smaller non-State armed groups, has driven widespread displacement.136 In Burkina Faso, this violence is mainly in the north of the country, at the borders with the Niger and Mali, and has resulted in serious humanitarian issues.

The number of new conflict displacements has grown, and in 2021, 682,000 new internal displacements resulting from conflict and violence brought the total number of IDPs to nearly 1.6 million.137 Further, a military coup in January 2022 caused additional new displacements, estimated by the national reporting mechanism, CONASUR, to be more than 160,000.138 The displacement effects of a second coup, which took place on 30 September 2022, are not yet clear.139

Key challenges for authorities and practitioners

The largest and most pressing challenge to date is finding suitable space to house over 1.5 million IDPs and an additional 3.5 million Burkinabè within the country in need of humanitarian assistance.140 According to the African Development Bank Group, two IDP camps have been constructed in the northeastern part of the country, with displaced persons from Barga and Titao, and which accommodate 6,000 and 10,000 IDPs, respectively. With a substantial need for increased capacity to house those fleeing conflict, and with hastily dwindling resources, the situation is looking more dire than ever.141

UNHCR and Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) both lack a significant portion of the funding needed to adequately provide their humanitarian response plans for 2022, with the former raising 20 per cent of its required budget,142 and the latter, only 15 per cent.143 As a result, shelter, food and medical assistance have been drastically reduced and civilians are lacking needed humanitarian aid.

Currently, 60 per cent of the country is under the Government’s control;144 this, coupled with the two coups in 2022, have generated high levels of instability in the country, which in turn risks increasing violent extremism and aggravating humanitarian needs. Following the September 2022 coup, the United Nations Secretary-General called on all actors to engage in productive dialogue.145

Good practices

In early 2021, the African Development Bank Group launched the Emergency Humanitarian Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons, which incorporated a grant of USD 500,000 for the construction of additional shelter and the provision of food and other essentials to 40,000 individuals.146 While a step in the right direction, the country will undoubtedly need further international assistance to support the one in five Burkinabè in need of humanitarian aid.147 According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) nearly three quarters of all households displaced in the country have been displaced for more than 12 months, and 34 per cent of them for more than 24 months.148

Improvements in coordination have allowed for the ability to respond to the humanitarian situation to be strengthened in many ways. Through a bolstered focus on methodology, which includes geographic analysis and community needs (like food, shelter, education and health) in a given area. This coordination also engages directly with national structures, to determine the functionality of resources and weak points to be addressed.149 Humanitarian coordination has also successfully been seen in certain instances, such as in the case of USAID, local NGOs and the World Food Programme working together to address malnutrition through the provision of emergency food assistance.150

Country case study (Asia): the Philippines. Initiatives to counter human trafficking

Sources: (a) UN DESA, 2022; (b) UNDP, 2020; (c) World Bank, n.d.; (d) UN DESA, 2021; (e) UNHCR, n.d.; (f) IDMC, 2023.

Major impacts on populations

In July 2022, for the seventh year in a row, the Philippines was ranked Tier 1 in the US Department of State’s trafficking in persons (TIP) report,151 which acknowledges high levels of compliance with the minimum standards to eradicate the trafficking of human beings set out under the United States Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000.152 The Philippines has introduced effective counter-trafficking initiatives in order to quell labour and sex trafficking present in the country. National counter-trafficking legislation was adopted in 2003,153 in the form of the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act, and the subsequent establishment of the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking. The legislative framework severely penalizes perpetrators of all forms of trafficking and formally recognizes the vulnerability of those trafficked.154

In 2022, the Philippines identified 1,802 victims of trafficking, of whom nearly 70 per cent were female (1,251) and 31 per cent (551) were male.155 According to the TIP report for 2022, trafficking over the course of the last five years has had a propensity to target not only the most vulnerable within the Philippines, but also Filipino nationals abroad.156 Women and children are often recruited into trafficking networks as sex workers, domestic workers and in other forms of forced labour, while men and boys tend to be recruited into forced labour in the agricultural, fishing and construction sectors.

Key challenges for authorities and practitioners

Specific challenges that authorities and practitioners face in the fight against trafficking include effective criminalization of traffickers and trafficking operations, as well as ensuring that sufficient resources are provided to both government authorities and organizations that are leading the charge of civil society actors against trafficking.

The 2022 TIP report recommends the overall expansion of resources dedicated to law enforcement, as well as the widening of judicial facility and capacity, so that traffickers can be promptly convicted and thus indicted for their crimes. Impediments to convicting traffickers were traced to slow-moving courts, lack of effective training of court officials and a limited number of prosecutors to try cases. Additional recommendations include putting greater emphasis on inter-agency and inter-organizational collaboration to provide support, including funding, to NGOs in their specialized programming and reintegration efforts. These include job training and placement for adult victims, as well as psychological and physical support for all victims.157

Good practices

While the defence and support of victims has always been central to rehabilitation and reintegration, the 2022 TIP report found the Philippines to have advanced in this regard as compared to past years. First, victims who served as witnesses to trials and suffered further trauma were provided specialized support and assistance throughout the entire criminal justice process. In 2020 and 2021, 11 trafficking victims (in 2020) and 1 (in 2021) were placed into witness protection programme to ensure their physical safety and as recognition of the risks associated. Second, police and prosecutors continued to prioritize recorded rather than live testimony in courtrooms, to ensure that benevolence is foregrounded towards victims of trafficking. Furthermore, the use of other forms of evidence, such as digital tracing and financial records have been incorporated into court proceedings that once depended heavily on testimony from victims.

Having been approved by law in December 2021 and put into effect in February 2022, the Department of Migrant Workers is a new government agency that has been created as a result of the merging of seven previous agencies. Its main task is the employment and reintegration of Filipino workers.158 The department will become fully operational in 2023 and will serve to maximize job opportunities for Filipino citizens upon their return from abroad and to stimulate national development after a two-year, COVID-19-induced slump.159 This may in the future facilitate the implementation of the TIP report recommendation regarding support for labour market reintegration for victims of human trafficking.

Country case study (Oceania): New Zealand. Multiculturalism and integration to counter extremist violence

Sources: (a) UN DESA, 2022; (b) UNDP, 2020; (c) World Bank, n.d.; (d) UN DESA, 2021; (e) UNHCR, n.d.; (f) IDMC, 2023.

Major impacts on populations

New Zealand is a highly diverse country and, according to the 2013 census, over a quarter of the population identified with a non-European ethnicity.160 Diversity and inclusion policies and strategies make space for celebration of difference and inclusion of all citizens, such as the adoption of multiculturism in school curriculum and the inclusion of ethnic representation and sensitivity in the mandate of public media.161 Despite this, it has been documented that minority ethnic groups, such as Asians, experience harsh discriminations in everyday life.

On 15 March 2019, the country’s southern city of Christchurch saw violent terrorist attacks take place in two mosques, killing a total of 51 people.162 A country in grief has since attempted to uncover the reasons for such violence, and to find ways to combat it, with some arguing that counter-terrorist efforts in the country focused on Islamic terrorism while ignoring evidence of growing support for white supremacist ideology.

Key challenges for authorities and practitioners

The incorporation of preventative measures that seek to combat violent extremism within the country can be seen clearly in the country’s practice of migration integration. New Zealand Immigration follows a settlement programme that focuses on five core outcomes, and each step is deemed essential for holistic integration: employment, education and training, English language, inclusion, and health and well-being.163 One of the main challenges faced by authorities and practitioners to date is how to maintain the country’s multicultural demographic whilst supporting all ethnicities to experience the same degree of integration. According to a 2021 survey on community perceptions of migrants and immigration, New Zealanders’ perception of their country as welcoming to migrants decreased from 82 per cent in 2011 to 66 per cent in 2021. The core reasons identified for this decline were racism and discrimination.164

With the aim of quelling extremism within different communities of New Zealanders, the Prime Minister committed authorities and government officials to tackling the problem from all angles. Addressing the growth of violent extremism through online channels, the Government (with the Government of France) launched the Christchurch Call to Eliminate Terrorist and Violent Extremist Content Online, building upon the tech sector’s Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism.165

Good practices

In the wake of the Christchurch events, New Zealand’s Counter-terrorism Coordination Committee developed a national strategy aimed at countering terrorism and violent extremism through a framework that begins with an aim of reduction and then moves onto themes of readiness, response and recovery.166 In the categories of readiness, response and recovery, a victim-centred approach is adopted, foregrounding the importance of partnership in the readiness both to respond and to recover.167 Key messages included in this national strategy are the strengthening of social inclusion, safety and equal participation.168

In June 2022, the Prime Minister launched the Centre of Research Excellence for Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism, or He Whenua Taurikura (in Māori), which translates to “a country at peace”.169 Here, independent and New Zealand-specific research into the causes and effects of violent extremism and terrorism is funded, so that a strong stance towards prevention can be taken in the island nation. And to combat the spread of racism, the country has begun the National Action Plan Against Racism, which directly reflects the country’s multicultural history, the ongoing path of diversity and the trajectory of New Zealand as a country that will lead the charge against racism in its many forms around the world.170 With local communities, businesses, institutions and individuals in the forefront, workshops are sponsored around the country to engage directly with definitions and practices of xenophobic behaviour and belief systems, as well as with national and international support mechanisms that protect all individuals from forms of harm, discrimination and violence.171