World Migration Report 2024: Chapter 3

Latin America and the Caribbean

Migration to Northern America is a key feature in the Latin America and Caribbean region253. The latest available international migrant stock data (2020)254 show that over 25 million migrants had made the journey north and were residing in Northern America (Figure 13). As shown in the figure, the Latin American and Caribbean population living in Northern America has increased considerably over time, from an estimated 10 million in 1990. Another 5 million migrants from the region were in Europe in 2020. While this number has only slightly increased since 2015, the number of migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean living in Europe has more than quadrupled since 1990. Other regions, such as Asia and Oceania, were home to a very small number of migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020 (over 400,000 and 200,000 migrants, respectively).

The total number of migrants from other regions living in Latin America and the Caribbean has remained relatively stable, at around 3 million over the last 30 years. These were comprised mostly of Europeans (whose numbers have declined slightly over the period) and Northern Americans, whose numbers have increased. In 2020, the numbers of Europeans and Northern Americans living in Latin America and the Caribbean stood at around 1.4 million and 1.3 million, respectively. Meanwhile, around 11 million migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean originated from other countries in the region.

Source: UN DESA, 2021.

Notes: This is the latest available international migrant stock data at the time of writing. “Migrants to Latin America and the Caribbean” refers to migrants residing in the region (i.e. Latin America and the Caribbean) who were born in one of the other regions (e.g. in Europe or Asia). “Migrants within Latin America and the Caribbean” refers to migrants born in the region (i.e. Latin America and the Caribbean) and residing outside their country of birth, but still within the Latin America and the Caribbean region. “Migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean” refers to people born in Latin America and the Caribbean who were residing outside the region (e.g. in Europe or Northern America).

The proportion of female and male migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean is largely about equal in the top countries of destination. The exception is the Dominican Republic, where the share of male immigrants is significantly higher than that of females. Among the top countries of origin, most have a slightly higher share of female than male emigrants, with countries such as the Dominican Republic, Brazil and Peru having the largest proportions.

Source: UN DESA, 2021.

Notes: This is the latest available international migrant stock data at the time of writing. “Proportion” refers to the share of female or male migrants in the total number of immigrants in destination countries (left) or in the total number of emigrants from origin countries (right).

Venezuelans continued to be among the largest population displaced across borders in the world in 2022 (Figure 15).255 At the end of 2022, there were more than 234,000 registered Venezuelan refugees and over 1 million with pending asylum cases. Other countries in the region, such as Nicaragua, Honduras and Cuba are also the origin of a significant number of asylum-seekers. Peru, Mexico, Brazil and Costa Rica host some of the largest numbers of asylum-seekers in the subregion, as reflected in Figure 15.

Source: UNHCR, n.d.a.

Notes: “Hosted” refers to those refugees and asylum-seekers from other countries who are residing in the receiving country (right‑hand side of the figure); “abroad” refers to refugees and asylum-seekers originating from that country who are outside of their origin country. The top 10 countries are based on 2022 data and are calculated by combining refugees and asylum-seekers in and from countries. Please refer to endnote 255 on the issue of categorization of displaced Venezuelans.

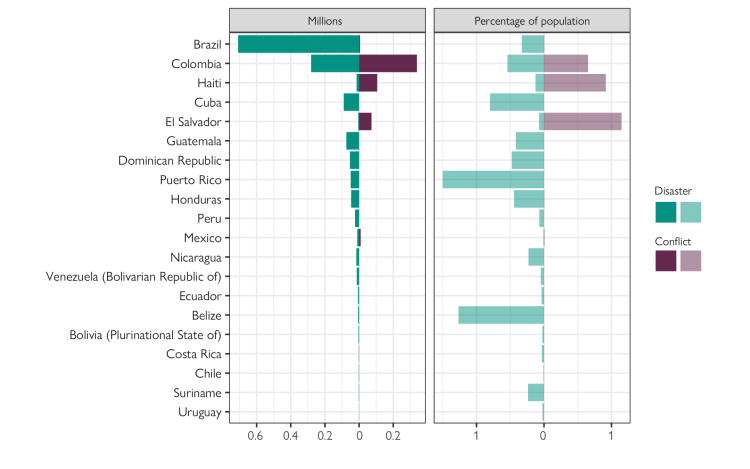

Disasters triggered some of the largest internal displacements in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2022 (Figure 16). Brazil, with 708,000 displacements largely due to floods caused by heavy rains, had the largest number of disaster displacements in the region. Colombia and Cuba recorded the second and third largest numbers of disaster displacements in Latin America and the Caribbean (281,000 and 90,000, respectively). Most displacements in Colombia were triggered by floods, while those in Cuba were largely related to Hurricane Ian. The largest conflict displacements in the region were concentrated in Colombia and Haiti, which recorded 339,000 and 106,000 displacements respectively.

Source: IDMC, n.d.; UN DESA, 2022.

Notes: The term “displacements” refers to the number of displacement movements that occurred in 2022 not the total accumulated stock of IDPs resulting from displacement over time. New displacement figures include individuals who have been displaced more than once and do not correspond to the number of people displaced during the year. The population size used to calculate the percentage of new disaster and conflict displacements is based on the total resident population of the country per 2021 UN DESA population estimates, and the percentage is for relative illustrative purposes only.

Key features and developments in Latin America and the Caribbean256

South America

Intraregional migration in South America, including for labour, remains high, while recent policy changes in some countries could have far-reaching implications for migrants in and outside the subregion. Over recent years and decades, free movement arrangements between countries in the subregion have made it possible for migrants to move to other countries within South America, mainly for work. Some of these include the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), comprising Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela,257 as member States, and the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru and Suriname, as associated States, and the Andean Community’s Migration Statute, the full members of which include the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.258 MERCOSUR has been key in opening up regular channels for South Americans to move to countries such as Argentina and Uruguay, while also playing a major role in facilitating regular migration and residence in these countries.259 Argentina had the largest number of immigrants in South America in 2020 (over 2 million), with most coming from countries within the subregion such as Paraguay and the Plurinational State of Bolivia.260 Colombia had nearly 2 million international migrants in 2020, and like Argentina, most were from within South America, particularly from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Ecuador.261 Chile had the third largest number of international migrants in South America in 2020, with more than 1.6 million residing in the country.262 Some countries in South America have undergone major migration policy changes in the last two years, with potentially significant implications for migrants. In 2023, Brazil rejoined the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, following a change in government, a decision that was welcomed by the United Nations Network on Migration as reviving the country’s “commitment to protecting and promoting the rights of all migrants living in Brazil as well as the more than four million Brazilians living abroad.”263 Chile, on the other hand, which has experienced a significant increase in the number of immigrants over the last 30 years, enacted new and restrictive immigration reforms in 2021 which have included new requirements that could make it more difficult for migrants to obtain residence permits from inside the country, while also allowing authorities to send back undocumented migrants who get into the country.264 This process has, for example, resulted in flows of Haitian migrants with children born in Chile towards other countries in the region and also towards Northern America.

The situation of Venezuelan migrants (including refugees) remains challenging, with millions continuing to experience the impacts of their displacement. By end of March 2023, there were more than 7 million Venezuelan refugees and displaced migrants globally, with the vast majority – more than 6 million – hosted in countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.265 By May 2023, Colombia was home to the largest number of Venezuelans (over 2.5 million), followed by Peru (more than 1.5 million) and Ecuador (around half a million).266 Chile and Brazil also host significant numbers, both more than 400,000.267 Several countries have provided asylum to Venezuelans and many have implemented arrangements to enable their stay and allow access to documentation and basic socioeconomic rights.268 More than 211,000 Venezuelans had been granted refugee status by March 2023; more than 1 million had lodged claims for asylum; and over 4.2 million had been issued residence permits or other types of stay arrangements.269 By the end of 2022, 1.6 million Venezuelans had temporary protection permits in Colombia, while 2.5 million had completed the pre-registration for temporary protection status in the country.270 By end of the same year, Peru had granted humanitarian residency permits to 79,600 Venezuelan asylum‑seekers and temporary residence permits to nearly 225,000 Venezuelans in an irregular migratory situation.271 Many Venezuelans, however, remain undocumented, preventing them from accessing job markets and social services, although countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Uruguay and others have moved to regularize millions of them.272 Despite the challenging conditions in which many continue to live, Venezuelans are also making significant contributions to their host countries, including as entrepreneurs and by creating jobs for themselves and locals in countries such as Colombia and Argentina.273 Many are also helping to fill key labour gaps, including, for example, in Peru’s health-care sector.274

Migration dynamics in parts of the subregion continue to be affected by internal instability and insecurity, with millions of people displaced as a result. In Colombia, while peace negotiations are ongoing, displacement due to internal violence continues, particularly in areas disputed or controlled by armed groups. At the end of 2022, 339,000 displacements due to conflict and violence had been recorded in Colombia and the country had nearly 5 million conflict IDPs.275 Fighting among armed groups intensified in 2022, contributing to further displacement. High levels of civilian targeting was also evident in the same year, with violence aimed at civilians accounting for more than 62 per cent of all organized political violence events in the country and more than 70 per cent of fatalities.276 Women and girls continue to be subjected to very high levels of violence in the subregion, and in Colombia many have suffered the long-term effects of gender-based violence, such as sexual harassment, human trafficking and rape.277 Insecurity and a surge in violence in Ecuador, particularly in the coastal region including in the country’s most populous city of Guayaquil, has forced many Ecuadorians to flee the country.278 The current wave of violence is largely driven by international criminal networks and gangs vying for territorial control over drug trafficking routes.279 The violence – combined with a dire economic situation that has left many in poverty – has resulted in a significant increase in the number of Ecuadorians leaving the country, often via Colombia and through the Darien Gap in the hopes of reaching the United States.280 As the number of Ecuadorians leaving the country has increased, thousands have been expelled in recent years under Title 42 or deported to Ecuador.281 Between January and April 2023, more than 11,000 Ecuadorians were expelled from the United States under Title 42.282

South America faces daunting challenges related to environmental degradation, disasters and climate change – including displacement – aggravating conditions in several countries already experiencing crises related to conflict and violence. Recent reports, including from the World Meteorological Organization and IPCC, show that in addition to climate change impacts such as the rise in sea levels – especially along the Atlantic coast of South America – some countries such as Peru have also seen glacier retreat while at the same time drought conditions have negatively impacted crop yields in the subregion.283 Indeed, the impacts of climate change are disrupting people’s livelihoods, compelling some to migrate from their places of origin.284 In a country such as Ecuador, it is predicted that environmental factors are likely to enhance both internal and international migration, while Peru has already advanced legislation on planned relocation – particularly along Peru’s rainforest rivers – as a solution and response to the adverse impacts of climate change.285 Moreover, climate-change-linked extreme weather events continue to contribute to displacement, in a subregion already dealing with conflict and violence and other socioeconomic and political factors that have driven millions of people from their homes and communities. In Brazil, floods were largely responsible for triggering more than 700,000 displacements in 2022.286 Rain and floods were also responsible for most of the 281,000 disaster displacements in Colombia in 2022.287 In early 2023, a state of emergency was declared in Peru after cyclone Yaku caused widespread flooding in the country’s northern region, resulting in deaths, destruction of property and displacement.288 Meanwhile, wild fires in Chile that started in January 2023 destroyed thousands of houses and prompted the evacuation of more than 7,500 people.289 Some countries in the region, in recognition of the climate change impacts on migration and displacement, have responded by offering avenues for protection for people who have been displaced by disasters. In May 2022, Argentina “adopted a new humanitarian visa pathway for people from the Caribbean, Central America and Mexico who were displaced due to natural events.”290

The number of migrants transiting through the subregion toward the United States continues to be high and has increased in diversity. The northern part of South America is a key transit area, with migrants from within and beyond the subregion – often assisted by smugglers – passing through and taking risky journeys north through Central America in the hope of reaching Northern America. Many migrants cross from Colombia to Panama through the Darien Gap (which traverses both countries), a dense tropical forest that takes migrants days to travel through, often with inadequate preparation and no access to water, health services or food.291 IOM documented 36 deaths in the Darien Gap in 2022, although this number is likely a very small fraction of the number of deaths that take place, since many deaths go unreported and migrants’ remains are also often not recovered.292 In addition to being a key destination country, particularly for migrants from within the subregion, Ecuador became a key entry point to South America for migrants of increasingly diverse nationalities, who transit through the country on their way to other destinations, particularly northward to the United States.293 Indeed, many migrants try to reach the United States via the Andean region–Central America–Mexico migratory corridor.294

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in extraregional migrant arrivals to South America, many with hopes of reaching Northern America. Migrants from regions such as Africa and Asia are behind some of this increase and often arrive in the subregion through regular means – either with a visa or in some cases a visa is not required.295 In 2022, around 10 per cent of migrants who crossed the Darien Gap were from Africa and Asia.296 While the desired final destination for many of these migrants is the United States or Canada, some eventually remain within countries in South America, either by choice or circumstance, as the journey northward is often difficult and expensive.297 There are often significant challenges related to the integration and social cohesion of these migrants, with some ending up in precarious working and living conditions. Language and cultural barriers add to these difficulties, making it harder for these migrants to integrate compared to others from within the region. While several countries have implemented a range of measures to facilitate their regularization and integration, many migrants still struggle, and obstacles still remain when it comes to accessing economic and social rights.298

Central America

Central America continues to be a major area of origin and transit for migrants trying to reach the United States. After a decline at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, irregular migration to and from the subregion rebounded in 2022 to pre-pandemic levels, with smuggling networks stepping up their operations.299 Since the start of 2022, there has been a significant increase in the number of migrants transiting through the Central America subregion, including through the countries of Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. More than half a million migrants who arrived at the United States border in the 2022 financial year were from three Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras). Countries such as Panama and Mexico have also experienced a surge in irregular migrants, increasing by 85 and 108 per cent respectively by August 2022.300 Criminal violence, political instability and poverty remain some of the biggest drivers of irregular migration from the subregion, with many migrants experiencing significant risks and dangers, including extortion, sexual violence and separation from families.301 Over the years, and as authorities cracked down on sea and air travel from the subregion, the Darien Gap – a treacherous remote jungle in Panama that connects South and Central America – has become a major transit area, with tens of thousands of migrants journeying through it annually. In 2022, many were Venezuelan (over 150,000), Ecuadorian (around 29,000) and Haitian (more than 22,000).302 The number of children trekking through the Darien Gap also increased significantly in 2022; between January and October 2022, more than 32,000 children travelled through the route, with more than half registered in Panama younger than 5 years old.303 Overall, there were over 248,000 migrants who entered Panama in 2022 at the Darien Gap border.304 More recent figures show a continuation of this trend, with many people continuing to trek through the Darien Gap in 2023. In just the first nine months of 2023, over 390,000 migrants had passed through the Darien Gap from Colombia to Panama, most of them from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Ecuador and Haiti.305

Across the subregion, violence – particularly gang-related violence – has resulted in a surge in displacement, forcing hundreds of thousands of people from their homes, communities or countries. In parts of Central America, such as Nicaragua and Honduras, the ever-deteriorating security situation, with crime and violence perpetrated by gangs and drug cartels – in addition to acute inequalities – has led many people to leave their homes. There were more than 665,000 refugees and asylum-seekers from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras worldwide at the end of 2022.306 These three countries also have some of the highest homicide rates in the world, as well as some of the highest incidents of sexual violence and femicide.307 However, there has been a significant decline in murders in El Salvador over the last two years as the Government has cracked down on gang violence.308 Gender-based violence, recent studies have found, is a major contributing factor to emigration from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico, and forces many adolescent girls to embark on dangerous journeys in search of safety.309 Criminal organizations that operate within and beyond the subregion often take advantage of the desperation of many and are heavily involved in both migrant smuggling and trafficking.310 At the end of 2022, Guatemala and Honduras each had more than 240,000 people living in internal displacement due to conflict and violence, while El Salvador had 52,000.311

Now the second largest recipient of international remittances in the world (after India), Mexico’s large diaspora continues to remit funds to their families and friends. China had long been the second largest recipient of international remittances in the world, but it was surpassed by Mexico in 2021, with the Central American country estimated to have received more than USD 61 billion in 2022.312 Compared with 2021, remittance flows to Mexico increased by 15 per cent, in part due to increased transfers to transit migrants – whose numbers have increased recently – and the decline in unemployment for Hispanics in the United States in 2022.313 Remittances are also a major source of foreign exchange for other Central American and Caribbean countries, and represented a lifeline during the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely affected them. While relatively small in terms of volume compared to flows to a country such as Mexico, remittances make up large shares of GDP in Honduras (27%), El Salvador (24%), Nicaragua (20.5%) and Guatemala (19%).314

Prone to disasters linked to climate change such as floods and tropical storms, several countries in the subregion have been identified as some of the most vulnerable to extreme climate events. The European Commission’s 2022 INFORM climate change index shows that countries such as Honduras, Guatemala, Panama, Nicaragua and El Salvador are among the most vulnerable to climate shocks.315 Disasters fuelled by climate change, such as Hurricanes Iota and Eta in late 2020, have also led to food insecurity in the subregion, with millions of people in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala experiencing high levels of food insecurity as a result.316 The ever-frequent disasters have, in addition, led to significant displacement. In late 2022, tropical storm Julia resulted in deaths, destruction of property and the displacement of tens of thousands of people across several countries, including Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama.317 Guatemala accounted for the largest share (56%) of the 72,000 new displacements that took place across eight countries as a result of the storm.318 Tropical storm Julia made landfall just as several parts of Central America were still recovering from both Hurricanes Iota and Eta, complicating recovery efforts.319

Caribbean

Traditionally known for emigration, with a large number of people moving to countries outside the Caribbean, migration within the subregion is also common and well established. Most intraregional migration is related to labour, with higher income countries in the Caribbean often attracting migrant workers from neighbouring islands with lower wages and where employment opportunities are limited.320 A country such as the Bahamas, with a thriving tourism industry and higher wages, is a key destination for a significant number of migrants from the subregion. In 2020, the Bahamas had around 64,000 international migrants, with nearly 47 per cent from Haiti.321 Barbados, another high-income country, is also a destination for migrants from within the subregion, particularly those from Guyana and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, who comprised the largest share of immigrants in the country in 2020.322 Not all intraregional migrants go to high-income countries, however. In 2020, the Dominican Republic was home to nearly 500,000 Haitians.323 Haitian migration to the Dominican Republic has a long history, with many working in the construction and agriculture sectors.324 The number of people moving from Haiti to its Caribbean neighbour has increased in recent years as the political and security situation in Haiti has deteriorated. In response to the insecurity in Haiti and an increase in Haitians entering the country, in 2022, the Dominican Republic further tightened its border while also summarily deporting tens of thousands of Haitians, prompting international and human rights organizations to issue statements urging the Government to stop the forced return of migrants.325 In 2022, thousands of Haitians were repatriated to Haiti by air or sea from countries such as the United States and Cuba, and in April 2023 alone, over 10,000 Haitians were repatriated, with more than 9,700 repatriated from Dominican Republic alone.326

Gang-related violence and insecurity, political persecution as well as deteriorating economic conditions in some countries in the Caribbean have resulted in significant internal and cross-border displacement. In Haiti, the escalation of intergang violence, particularly in the capital Port-au-Prince, had triggered more than 100,000 internal displacements in 2022.327 Conditions in the capital continue to be characterized by kidnappings, racketeering, acute deprivation and widespread insecurity.328 While violence and insecurity in Haiti is not a new phenomenon, it has worsened since 2021, when the country’s president was assassinated.329 Criminal gangs control large swathes of the capital and women and girls have been the most affected. As the political and economic situation has deteriorated, there has been an increase in sexual violence as well as exploitation perpetrated by gangs against women and girls.330 In Cuba, a worsening economic situation – accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and tougher economic sanctions from the United States – have decimated the country’s economy, including key sectors such as tourism, leaving many people in deep poverty.331 As a result, hundreds of thousands of Cubans have left the country in the 2022 fiscal year: more than 220,000 encounters with Cuban migrants were reported at the United States border with Mexico.332 2022 saw the largest exodus of Cubans in more than 30 years, even bigger than the 1980 Mariel boatlift, when 125,000 Cubans arrived in the United States over a period of 6 months.333 While many Cubans have left due to economic conditions, some have fled the country for fear of persecution, as the Government cracked down on those who participated in 2021 protests, the largest protests in Cuba in decades.334 Some Cubans have attempted to reach the United States by sea – often on rickety boats – while others fly to either Nicaragua (which does not require an entry visa for visiting Cubans) or to a lesser degree Panama, and then ride buses up through Central America.335 There were more than 300 deaths and disappearances of migrants in the Caribbean in 2022, the highest number since IOM began collecting these data.336

Despite their relatively low contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, Caribbean nations are some of the most at risk from the impacts of climate change. With several small island and low-lying States, the Caribbean is extremely prone to natural hazards.337 Small island States face more frequent storms, rising sea levels and biodiversity loss.338 Some studies have projected that damages due to climate change in the Caribbean could increase from 5 per cent of GDP in 2025 to 20 per cent in 2100, if no measures are taken to blunt its impacts.339 Hurricane Ian, which made landfall in Cuba in September 2022, resulted in 80,000 displacements (largely pre-emptive evacuations). Meanwhile, Hurricane Fiona triggered 94,000 displacements, most of which took place in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico and resulted in floods and landslides.340 A recent report from the World Meteorological Organization argues that while drivers and outcomes depend highly on context, migration due to climate change is projected to increase on small islands, including in the Caribbean.341 Moreover, the recent IPCC assessment report also details that a 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature could lead to a 60 per cent increase in the number of people projected to experience severe water resource stress for Caribbean small island developing States (SIDS).342