World Migration Report 2024: Chapter 3

Europe

The latest available international migrant stock data (2020)210 show that nearly 87 million international migrants lived in Europe211, an increase of nearly 16 per cent since 2015, when around 75 million international migrants resided in the region. A little over half of these (44 million) were born in Europe, but were living elsewhere in the region; this number has increased since 2015, rising from 38 million. In 2020, the population of non-European migrants in Europe reached over 40 million.

In 1990, there were roughly equal numbers of Europeans living outside Europe as non-Europeans living in Europe. However, unlike the growth in migration to Europe, the number of Europeans living outside Europe mostly declined over the last 30 years, and only returned to 1990 levels in recent years. In 2020, around 19 million Europeans were residing outside the continent and were based primarily in Asia and Northern America (see Figure 9). As shown in the figure below, there was also some gradual increase in the number of European migrants in Asia and Oceania from 2010 to 2020.

Source: UN DESA, 2021.

Notes: This is the latest available international migrant stock data at the time of writing. “Migrants to Europe” refers to migrants residing in the region (i.e. Europe) who were born in one of the other regions (e.g. Africa or Asia). “Migrants within Europe” refers to migrants born in the region (i.e. Europe) and residing outside their country of birth, but still within the European region. “Migrants from Europe” refers to people born in Europe who were residing outside the region (e.g. in Latin America and the Caribbean or Northern America).

In Europe, the distribution of female and male migrants is about equal across both the top 10 countries of destination and origin. Unlike Africa and Asia – where most countries have slightly higher shares of male than female migrants – in Europe there are more countries with slightly higher shares of female than male migrants (in both the top destination and origin countries). Among destination countries, Ukraine has a significantly higher proportion of female immigrants than males when compared with other European countries. The Russian Federation and Ukraine also have the highest share of female emigrants among origin countries where the proportion of female emigrants is higher than males. Italy and Portugal are the only two origin countries with a larger share of male than female migrants.

Source: UN DESA, 2021.

Notes: “Proportion” refers to the share of female or male migrants in the total number of immigrants in destination countries (left) or in the total number of emigrants from origin countries (right).

The Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 resulted in one of the largest and fastest displacements in Europe since the Second World War. Millions of Ukrainians have been displaced to neighbouring countries, and by end of 2022, Ukraine was the origin of nearly 5.7 million refugees, the second largest number in the world after the Syrian Arab Republic (Figure 11). Close to 2.6 million Ukrainians were hosted in neighbouring countries such as Poland, the Republic of Moldova and Czechia, and another 3 million in other European countries and further afield. Germany hosts the largest number of refugees in Europe (around 2 million), 7 per cent of all refugees in the world. Most refugees in Germany at the end of 2022 originated from Ukraine and the Syrian Arab Republic. The Russian Federation, Poland and France hosted the second, third and fourth largest refugee populations in the region.

Source: UNHCR, n.d.a.

Notes: “Hosted” refers to those refugees and asylum-seekers from other countries who are residing in the receiving country (right-hand side of the figure); “abroad” refers to refugees and asylum-seekers originating from that country who are outside of their origin country. The top 10 countries are based on 2022 data and are calculated by combining refugees and asylum-seekers in and from countries.

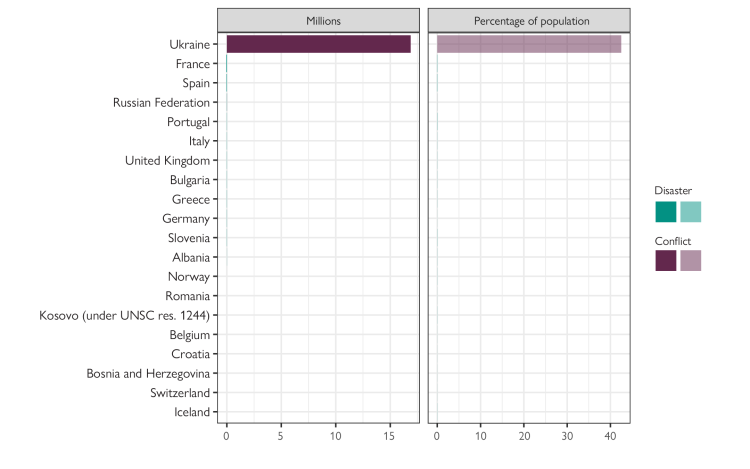

Ukraine recorded the largest internal conflict displacements in the world in 2022, the result of the Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion. Nearly 17 million displacements (around 40% of the country’s population) were recorded in Ukraine by the end of 2022, the largest figure the country has ever recorded (see Figure 12). The massive number of conflict displacements in Ukraine in 2022 was also the highest in the world. The largest disaster displacements in Europe occurred in France (45,000) and Spain (31,000); in both countries, these displacements were largely triggered by wildfires.

Source: IDMC, n.d; UN DESA, 2022.

Notes: The term “displacements” refers to the number of displacement movements that occurred in 2022 not the total accumulated stock of IDPs resulting from displacement over time. New displacement figures include individuals who have been displaced more than once and do not correspond to the number of people displaced during the year.

The population size used to calculate the percentage of new disaster and conflict displacements is based on the total resident population of the country per 2021 UN DESA population estimates, and the percentage is for relative illustrative purposes only.

Key features and developments in Europe212

South-Eastern and Eastern Europe

The Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which began in February 2022, has resulted in the largest displacement within Europe since the Second World War. In addition to civilians who have been injured or killed since the war began – more than 8,000 deaths and over 14,000 injured as of 9 April 2023 – millions of people have been displaced within Ukraine, while others have been forced to flee the country in search of safety and protection.213 By April 2023, more than 8 million refugees from Ukraine had been recorded across Europe, while nearly 6 million people had been internally displaced in Ukraine at end of 2022.214 Most refugees had fled to neighbouring countries such as Poland, Czechia, Bulgaria and Romania, among others.215 By April 2023, Poland was host to more than 1.5 million Ukrainian refugees.216 The overwhelming majority of Ukrainian refugees are women and children, as most men – between the ages of 18 and 60 – were required to remain in the country and fight. As the war continues, the situation in Ukraine remains dire for many, including those who remain in the country under threat from the fighting, while also having to contend with outages of water, electricity, heating and the disruption of key services such as medical care.217

Largely due to the lack of decent employment prospects and the search for better paying jobs, many people have left the subregion, often to work in Western and Northern Europe. Countries such as Albania and the Republic of Moldova are some of the hardest hit; around 40 per cent of Albania’s workforce, for example, is estimated to be working abroad,218 contributing to brain and brawn drain and putting pressure on local industries and economies that constantly lose workers in both low-skilled and high-skilled sectors. High rates of poverty, wage gaps between Albania and other countries in the region, significant corruption and clientelism, among other factors, contribute to people’s decisions to leave the country.219 A similar trend can be seen in the Republic of Moldova, with around a quarter of its “economically active” population working outside the country.220 The Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine that has resulted in a cost-of-living crisis across the world, including in countries in the subregion, has forced even more Moldovans to leave the country.221 Other countries such as Bulgaria and Serbia are no exceptions and continue to see many of their young people leave.222 While many who leave are regular migrant workers who end up working in the Russian Federation or in countries within Western and Northern Europe, there has also been an increase in the number of irregular migrants from some countries in the subregion. Thousands of young Albanians, for example, have resorted to taking arduous journeys to try and reach Northern Europe, especially the United Kingdom, with many risking their lives crossing the English Channel in small boats or inflatable dinghies.223

As many parts of the world experience declines in their population, countries in the subregion are among the most affected, prompting concerns and discussions about immigration policies. Due to sustained low levels of fertility and elevated rates of emigration, many countries are having to contend with shrinking populations, leading to labour shortages, including in key sectors, with significant short- and long-term implications for their economies. These realities have also put pressure on these countries’ pension systems. Several of the affected countries, including Poland, Serbia, Ukraine and Bulgaria, are among the countries the populations of which are forecast to shrink by 20 per cent or more over the next three decades.224 Immigration has long been a policy employed by countries – particularly those in Western Europe, Northern America and Australia – to reduce the economic and social effects of declining birth rates and ageing populations. While it is widely acknowledged that immigration is important in addressing the negative impacts of population decline in several South-Eastern and Eastern European countries, the approach has tended to focus on increasing birth rates (including through financial incentives). Immigration is often viewed with suspicion and, in several countries, even curtailed through restrictive immigration policies and political rhetoric meant to discourage migrants from either entering or settling in some of these countries.225

Irregular migration from, to and through South-Eastern and Eastern Europe, including by people from within and outside the subregion, remains a key challenge. Often with the assistance of smugglers, the subregion is a major transit area and characterized by mixed migration flows, particularly for migrants trying to reach Western and Northern Europe. The western Balkan route, referring to irregular arrivals in the European Union through the western Balkans, including via countries such as Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia, among others in the subregion, has seen an increase in arrivals since 2018.226 Serbia continues to be the main transit hub, with nearly 121,000 registrations in 2022.227 Upon arrival in the western Balkans, the routes most use are through North Macedonia, Serbia and then direct attempts to cross into the European Union across the Hungarian border.228 The three largest nationalities arriving in the Balkans include Afghans, Syrians and Pakistanis.229 The transit period of migrants passing through the western Balkans was shorter in 2022, with many spending fewer days in each country compared to previous years.230 Other non-Balkan countries in the subregion, such as Belarus, have also in recent years been transit areas for migrants attempting to reach the European Union with some pointing to the use of irregular migrants as a political weapon and leverage (the so-called “instrumentalization” of migrants).231

Northern, Western and Southern Europe

In March 2022, following the Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and subsequent displacement of millions of Ukrainians, the European Union took the unprecedented decision to activate a Temporary Protection Directive (TPD), granting Ukrainians fleeing the war a legal status that allows them to access a wide range of rights in European Union member States. The directive guarantees the same socioeconomic rights and services to those who have obtained legal status under the TPD in all European Union member States, such as access to medical care, accommodation, work, free movement as well as education.232 In some instances, displaced Ukrainians opted for a member State where they could apply for temporary protection, in recognition of their existing networks.233 Ukrainians under the TPD can also visit Ukraine, if they so choose.234 However, there has been concern that some aspects of the TPD, in terms of wording, are unclear, resulting in complications for some Ukrainians, particularly when it comes to keeping their status after short visits to Ukraine as well as accessing available assistance.235

Several countries across the region have passed or proposed new restrictive immigration and asylum laws while also implementing a range of measures widely viewed as undermining asylum and violating international law. Legislation introduced into Parliament by the United Kingdom Government in March 2023, for example, that would allow for the removal of people who arrive in the country irregularly and their being taken to a third country (such as Rwanda) for processing, has been widely criticized by civil society and international organizations. In response to the legislation, organizations such as UNHCR have argued that, if passed, it would breach the United Kingdom’s commitments under international law.236 The Illegal Migration Bill, it is argued, would deny protection to many people who genuinely need safety and asylum, thereby contravening the 1951 Refugee Convention, to which the United Kingdom is a signatory.237 IOM also expressed concern that parts of the Bill “would limit survivors’ ability to report trafficking and access assistance, which risks exacerbating the vulnerability of victims, giving traffickers more control over them and deepening risks of further exploitation.”238 Denmark has also sought to implement significant restrictions on immigration. Similar to the United Kingdom, in 2022 Denmark pursued an agreement with the Government of Rwanda to outsource asylum processing to the country.239 These plans were, however, put on hold in early 2023, with a new government in power.240 In Italy, a new decree – introduced at the start of 2023 and setting out a code of conduct for rescue of ships seeking to disembark in the country – has raised concerns, including from OHCHR, as potentially preventing “the provision of life-saving assistance by humanitarian search and rescue (SAR) organisations in the Central Mediterranean”, which could lead to more deaths.241

Irregular migration remains one of the most significant migration challenges for countries in the subregion, and continues to be characterized by mixed migration flows, often with the assistance of well-established smuggling networks. Calendar year 2022 saw the largest number of irregular arrivals since 2016, with more than 189,000 arrivals in Europe via land and sea.242 While there was a decrease, overall, in irregular border crossing at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, there was an uptick in arrivals in 2021 and a further increase in 2022.243 The largest number of irregular arrivals in 2022 came from Egypt (almost 21,800), the Syrian Arab Republic (nearly 21,000), Tunisia (over 18,000) and Afghanistan (more than 18,000).244 Smuggling networks play key roles in enabling attempts to reach Northern, Western and Southern Europe, often charging high fees, while also exposing migrants to a multitude of risks and abuses. Some States outside the European Union have also in recent years been blamed for encouraging and even facilitating irregular migration to the subregion, using migrants as leverage or pawns for political ends.245 In response, the European Commission introduced a proposal to tackle situations where State actors enable irregular migration for political purposes to destabilize the European Union, and allows member States to “derogate from their responsibilities under European Union asylum law in situations of instrumentalization of migration.”246 The proposal has been criticized by civil society organizations, with some arguing that it is akin to dismantling asylum in Europe by allowing member States the potential to opt in and out of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS).247

In recent years, several countries in the subregion have adopted feminist foreign policies, which have the potential to positively impact migrant women and girls across the world. Sweden was the first country in the world to adopt a feminist foreign policy, in 2014, although this policy was abandoned in late 2022 when a new government came to power.248 Several other countries, including some in Northern, Western and Southern Europe, have since adopted similar policies. Some of these include France (2019), Germany (2021), Luxembourg (2021) and Spain (2021).249 These policies cover a range of areas, including mainstreaming gender perspectives across all foreign policy actions and agencies, and advocating for progress in providing gender adequate resources to ensure gender equality as part of development and humanitarian aid.250 While the policies have been widely welcomed and have generated interest as a way to empower women and girls globally, some have also been criticized for neither directly mentioning immigration nor addressing the various needs of migrants and the specific contexts from which they come, as well as paying little attention to immigration as an issue of foreign policy.251 Outside Europe, Canada arguably has the most sophisticated feminist foreign policy, “the Feminist International Assistance Policy”, which, among other commitments, “advocates for progressive approaches to migration and refugee assistance.”252