World Migration Report 2024: Chapter 4

Appendix C

For the purposes of this chapter, in order to determine an estimated number of migrants who inhabit a jurisdiction due to factors not related to forced migration, we utilized the forced migration data base produced by UNHCR along with international migrant stock numbers produced by UN DESA.84 Since these United Nations agencies collect data and make estimations based on disparate methods, sources and time frames, it is worth mentioning a few details about the computations featured in this chapter.

For each country in each year, the stock of forced migrants – made up of those legally designated as refugees by UNHCR plus UNHCR’s estimate of asylum seekers – is subtracted from the overall migrant stock. In cases where a country’s number of forced migrants (from UNHCR) exceeds the total migrant stock of an origin or destination country, the number of “non-forced-migrants” is reduced to zero to avoid a nonsensical “negative” stock.

To calculate migrant stock as a proportion of population, different computations are required in the case of emigration (the movement of people away from an origin country) than in situations of immigration – the movement of people to a destination country. In both cases, we used migrant stock data and population data, published most recently by UN DESA in 2020.

In cases of immigration, calculating the migrant stock for an HDI classification follows the equation:

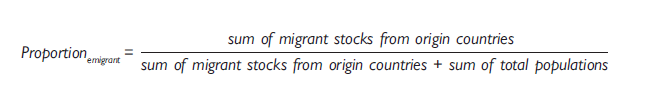

For cases of emigration, diaspora populations have to be included in the denominator of the formula to ensure correct proportionality. Thus, the equation for each HDI classification is:

Since the accurate, anonymous and consistent collection of migration flow data remains difficult, the use of migrant stock has become a standard, if indirect way to assess migration flows.85 As with previous studies using bilateral migrant stock data, we are bound by the same limitations, most prominent of which is an assumption that migrants are leaving their country of birth or citizenship, which might not always be the case.86 By measuring migrant stocks in discrete intervals over time, one has a broad sense of movements of people between places, at least in the form of snapshots over time. As noted by Clemens, measuring migrant stock in this way does not account for migrant deaths, one of the other pillars of demographic change. A more precise term for the calculations completed in this chapter would be to call this the “incidence” of migration. To avoid technical jargon for a broader readership, we have chosen to avoid this discussion in the main text, while recognizing the conceptual distinctions here.